On climate targets and practicalities

This week the European Parliament joined other democratic assemblies around the world in voting to declare that there is a climate emergency. At the same time there is an ongoing debate in the EU over whether the 2030 targets for emissions reductions should be increased from 50% to 55%. However, there are questions to be asked over whether this is really the right focus for this whole debate.

Now, first of all let me say that I do support the intent behind these ideas. Declaring a climate emergency is symbolically powerful and we should indeed be ambitious in our emissions reduction goals. But in the end do either of these two things have much practical impact? After all, recognising the climate emergency does not do much beyond state that we agree with the scientific consensus - a statement so obvious that when we frame it that way it is difficult not to wonder why we're even voting on it at all. And while the idea of raising our targets is good, it really won't do much for anyone if we don't have the accompanying debates (and more importantly, decisions) on how to reach them.

The reality is that while we discuss whether to increase the 2030 target from 50% to 55%, we're still not any further forward on how to actually reach the 50% target in the first place. Some countries such as Poland are not even on track to meet the current 2020 target (20% reduction), let alone a more ambitious target for 2030.

In this regard, what we really need are concrete measures and pieces of legislation that work to cut the use of fossil fuels and increase the use of renewables (as well as reducing overall energy consumption in some cases). Here, the recent EIB reform was likely much more significant than the Parliament vote on declaring a climate emergency. By phasing in a ban on funding for fossil fuel projects, the new EIB lending mandate will actively work to divert money away from fossil fuels. With less funding available for these projects, fewer will go ahead and so governments and private investors will be forced to conclude that renewables are the more economically viable projects. This is not to oversell the EIB reform as in practice most of the funding for energy generation projects in Europe comes from other sources, notably national governments, but it does point to the kinds of measures that we should be getting really excited about. The new Commission should therefore follow this up with similarly powerful ideas, such as phasing in a ban on coal mining and then another on shale oil, while implementing strict requirements on the kinds of gas that can be used. Reducing the use of cars in our cities, improving public transport and generally pedestrianising urban areas will also be important.

The targets are a useful benchmark by which we can measure our progress but in themselves they are not as important as the myriad of other debates and decisions that will underpin our ability to prevent further deterioration in our global environment. Therefore instead of investing significant energy in these debates, let's use our collective resources on more practical pieces of legislation and initiatives. Then, if we reach say 2025 and find that we are on track, nothing will stop us from raising our ambitions and setting higher targets.

In fairness the new Commission is only just getting started and still has time to push ahead with proposals for legislation that will really push Member States to shift towards renewables. But this will need to be a conscious choice and at times may require a degree of political confrontation. Many countries and certain political groups are resistant to these changes. If new Commission President Ursula von der Leyen shies away from these key battles, falling back on simple moral pressure, then we may well be disappointed by the pace of progress on climate change. But this does not mean simply deploying a big stick, a big carrot will be needed as well and perhaps the most concerning thing for the Commission's climate ambitions right now is the proposed scale of the fund that will be used to help those communities shifting away from traditional fossil fuel industries. The current proposal is fairly modest to say the least and the danger is that this will inevitably limit the scale of change that national governments are willing to undertake. We know that this climate shift is necessary but we also know it will be difficult. If we are not ready to provide solidarity as much as admonition then we will miss the opportunity to agree the political grand bargain that could unlock the major changes we need.

The European Parliament has already declared the presence of a climate emergency, now we need Europe's legislative institutions to get to the details and produce the laws we need to turn our concerns into actions.

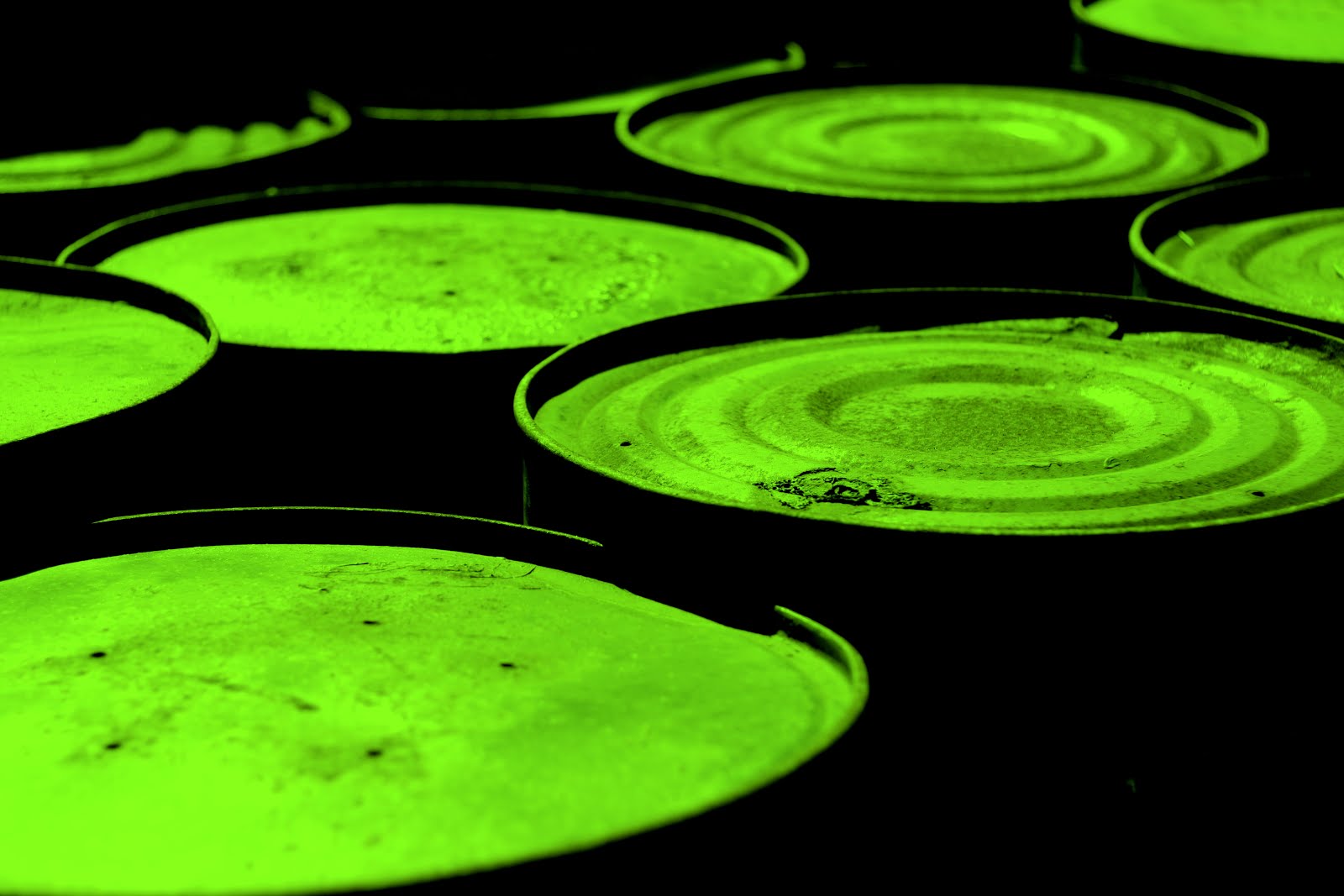

Image via Flickr

Now, first of all let me say that I do support the intent behind these ideas. Declaring a climate emergency is symbolically powerful and we should indeed be ambitious in our emissions reduction goals. But in the end do either of these two things have much practical impact? After all, recognising the climate emergency does not do much beyond state that we agree with the scientific consensus - a statement so obvious that when we frame it that way it is difficult not to wonder why we're even voting on it at all. And while the idea of raising our targets is good, it really won't do much for anyone if we don't have the accompanying debates (and more importantly, decisions) on how to reach them.

The reality is that while we discuss whether to increase the 2030 target from 50% to 55%, we're still not any further forward on how to actually reach the 50% target in the first place. Some countries such as Poland are not even on track to meet the current 2020 target (20% reduction), let alone a more ambitious target for 2030.

In this regard, what we really need are concrete measures and pieces of legislation that work to cut the use of fossil fuels and increase the use of renewables (as well as reducing overall energy consumption in some cases). Here, the recent EIB reform was likely much more significant than the Parliament vote on declaring a climate emergency. By phasing in a ban on funding for fossil fuel projects, the new EIB lending mandate will actively work to divert money away from fossil fuels. With less funding available for these projects, fewer will go ahead and so governments and private investors will be forced to conclude that renewables are the more economically viable projects. This is not to oversell the EIB reform as in practice most of the funding for energy generation projects in Europe comes from other sources, notably national governments, but it does point to the kinds of measures that we should be getting really excited about. The new Commission should therefore follow this up with similarly powerful ideas, such as phasing in a ban on coal mining and then another on shale oil, while implementing strict requirements on the kinds of gas that can be used. Reducing the use of cars in our cities, improving public transport and generally pedestrianising urban areas will also be important.

The targets are a useful benchmark by which we can measure our progress but in themselves they are not as important as the myriad of other debates and decisions that will underpin our ability to prevent further deterioration in our global environment. Therefore instead of investing significant energy in these debates, let's use our collective resources on more practical pieces of legislation and initiatives. Then, if we reach say 2025 and find that we are on track, nothing will stop us from raising our ambitions and setting higher targets.

In fairness the new Commission is only just getting started and still has time to push ahead with proposals for legislation that will really push Member States to shift towards renewables. But this will need to be a conscious choice and at times may require a degree of political confrontation. Many countries and certain political groups are resistant to these changes. If new Commission President Ursula von der Leyen shies away from these key battles, falling back on simple moral pressure, then we may well be disappointed by the pace of progress on climate change. But this does not mean simply deploying a big stick, a big carrot will be needed as well and perhaps the most concerning thing for the Commission's climate ambitions right now is the proposed scale of the fund that will be used to help those communities shifting away from traditional fossil fuel industries. The current proposal is fairly modest to say the least and the danger is that this will inevitably limit the scale of change that national governments are willing to undertake. We know that this climate shift is necessary but we also know it will be difficult. If we are not ready to provide solidarity as much as admonition then we will miss the opportunity to agree the political grand bargain that could unlock the major changes we need.

The European Parliament has already declared the presence of a climate emergency, now we need Europe's legislative institutions to get to the details and produce the laws we need to turn our concerns into actions.

Image via Flickr

Comments

Post a Comment