Considering the dispute on the Northern Ireland Protocol

Weren't we told that a referendum would let us stop 'banging on about Europe'? Wasn't Brexit going to be 'done'? As we again return to the problems Brexit has created for the status of Northern Ireland, you'd be forgiven for thinking that these prognoses were not wholly correct.

These past few weeks, we have witnessed a steadily escalating conflict over the implementation of the Northern Ireland Protocol. Part of the 'great deal' that was sold to the British public not so long ago, the Protocol has now become reviled by many leading Brexiteers. In truth, they may have been happy to accept it if the most hardline elements of the Northern Irish unionist community had not mounted such a strong opposition. Starting with governing members of the DUP, and spreading out across unionism, there have been attempts to sabotage the Protocol, protests and acts of violence.

In response, Brexiteers have chosen to avoid facing down the unionist, to explain why the Protocol is a necessary compromise that the government needed to agree to in order to avoid worse outcomes for the UK, and have instead placed the blame on the EU. As such, the EU is now being held as solely responsible for the discontent in Northern Ireland because it (we are told, unreasonably) insists on implementing the deal that was agreed not 6 months ago.

This means that many grace periods for various forms of trade between Great Britain and Northern Ireland will very soon come to an end. This includes the now infamous sausages (specifically if they haven't been frozen for transport). The impending cliff-edge (how we have missed Brexit cliff-edges in our lives) means that tensions between the UK and the EU have escalated dramatically to the point where the UK government has effectively indicated that it will not uphold some of the key terms of the agreed treaty, will unilaterally allow the trade to go ahead and demands that the EU make concessions if there is to be any agreement.

At the core of the argument coming from the dusty corridors of Westminster is that the EU has not offered sufficient flexibility. Goods from Great Britain are argued to not be any kind of threat to the EU Single Market and therefore it's simply unreasonable to expect any checks at all between Great Britain and Northern Ireland. As an argument, it is beguilingly simple. And the pages and pages worth of chatter about how the 'Great British sausage' is perfectly fine and those 'barmy Brussels bureaucrats' are simply out of their minds and/or drunk on power and/or out to destroy said 'Great British sausage' demonstrate the power of that simplicity (as well as the UK media's general inability to discuss complex issues in a serious manner when they can be dumbed down into quick soundbites).

Before turning to whether the EU position is in fact as crazy as some would imply, it's perhaps worth asking whether the Westminster position is reasonable. The truth is that it has serious shortcomings.

For one thing, it is not true that the EU has offered no compromise or flexibility. The Northern Ireland Protocol was freely agreed between the UK and the EU. After months and months of agonising over how to make the desire of Westminster Brexiteers for the hardest form of Brexit compatible with the needs of the Northern Irish peace settlement, the UK and Ireland negotiated an outcome that both said they could accept. The EU then backed up that Irish position, and the deal was done. We were not forced, we were not coerced.

Having signed and ratified this international agreement, for all the world to see, there was then a good amount of time given to actually implement all the terms of this deal. Everyone had known that there would be some disruption to Great Britain-Northern Ireland trade, so the first months of this year, once the Brexit terms had kicked in, were set up as grace periods. This was to give companies time to retool their supply chains and ensure that shelves in Northern Ireland would not be left empty.

But of course, this is not the kind of flexibility Brexiteers now have in mind. Because their actual demand isn't for flexibility in implementing the Protocol. Their demand is, at least in part, to not implement it at all.

While the Protocol was inevitably a compromise, containing aspects which the UK would have preferred to avoid, the government decided that these drawbacks were ultimately acceptable in the name of other policy goals. Now the UK is turning around and saying that those parts where we compromised should simply be scrapped and that the EU is the unreasonable one for not just going along with this u-turn.

The arguments coming out of Westminster are not even arguing that the EU is wrong about the Protocol, simply that the EU is being either 'imperialist' or 'legalistic'. Indeed the actual text of the Protocol seems to be virtually absent from the discussion currently unfolding in London. If the EU is n fact implementing the agreement in an excessive way (seemingly the implication of the former accusations), surely we can produce a legal argument that the EU has overstepped the bounds of our treaty (which is of course binding on the EU as well). In reality, we are not hearing journalists, commentators or politicians pulling out the relevant words from this international treaty and giving us a well-grounded argument for why our interpretation is correct and the EU's has gone awry. This is not a disagreement about implementation, it is a decision to not implement this agreement and to insist on a new one.

And maybe Theresa May was right. Perhaps there really was no way that a British Prime Minister could sustainably agree to this kind of deal. It is possible, by some stretch of the imagination, to suppose that we agreed to this international treaty and then ratified it in some kind of fit of madness. More prosaically, perhaps we simply changed our minds - this happens in democracies.

But if any of these explanations are true then why should we not be honest about it? Throw our ends up and admit we got it wrong. This would be embarrassing, no doubt, but an explanation that the strength of feeling and volatility in the unionist community was underestimated by Westminster would at least be credible and be a reasonable starting point for re-engaging in the EU.

As it is, far from asking for more compromise, the UK position is to unpick and unravel a compromise that is already in place with little in the way of an offer to the EU. Is it any surprise that the EU is not responding well to this demand? Why would anyone? If we won't implement the last deal we made, this does not set us up as a reliable partner for any future negotiation or compromise. This is precisely Macron's point when he says "nothing is negotiable" - it is not obstinate legalism but an argument about the importance of trust in international relations.

And the absence of a firm footing for the UK's demands is not a minor point. In reality it cuts down any possibility of Brexiteers' preferred alternative making any headway.

Commentators seem to suggest that the reasonable course of action for the EU would be to simply trust that the UK will play within the rules in practice, even if there are no legal mechanisms to ensure this is so. The argument runs that the UK is basically one of the world's good guys and so there is no need for such messy things as written treaties and border checks when dealing between honest gentlemen (the 'good chap' theory of government, as it is known).

This attitude, however, is sadly detached from the reality of the UK's image in Europe. Even without the latest reversal in position on the Protocol, trust has been burned consistently since 2016 and the UK-EU relationship is already based on very rocky foundations. This does not mean we are put on a level with Russia or Iran, but it does mean our word is not taken as an inviolable promise. Voices in our public arena regularly denigrate the EU and some openly call for or wish for the EU's failure and end - a fair few others do so implicitly. There is an open atmosphere of hostility towards the EU in UK politics that is not only tolerated but often rewarded. This does not build trust. And this lack of trust was the whole reason that a solid, written agreement to manage relations between the two sides was needed in the first place (a suspicion more than confirmed for the EU by the dispute over the Internal Market Bill). If we are to get to a place where the UK is seen as a trusted partner, the very minimum would be to fully implement the deals we already signed up to, but even this might not be enough without a wider seachange in the attitudes of mainstream commentary towards our neighbours.

Even if we imagined some parallel world where UK-EU relations were substantially better than they are today (maybe even good, if we dare push the boat so far out), the UK is still making a very big ask. Far from being treated 'like any other country', historically a point that Brexiteers insisted should be at the heart of the UK-EU relationship, the UK demand would entail being treated unlike any other country, given exceptionally generous treatment. Indeed, the approach of just dispensing with checks for certain food imports is not an approach that the UK itself intends to take.

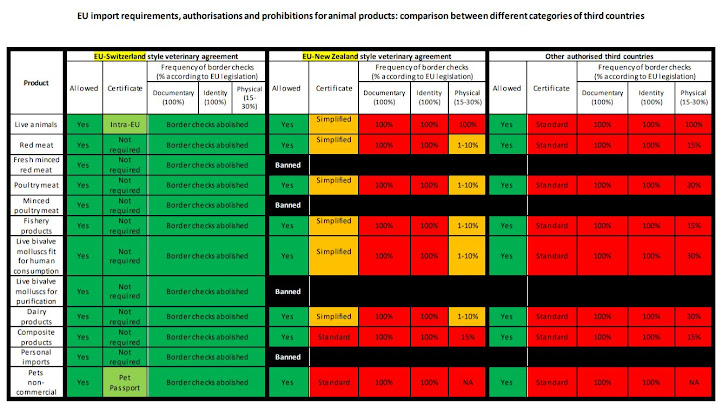

As the chart below shows, there are three options the EU currently uses. One is the generic 'third country' option. The second is the New Zealand model, whereby there is some limited equivalence based on trust and a mutual approach of high standards. The third is the Swiss model, where Switzerland aligns with the relevant EU rules to guarantee an absolute minimum of checks, abolishing them in many cases.

In other words, the established trust-based model the UK is banking on does not go nearly far enough to address the concerns of unionists in Northern Ireland. Many of the sticking points of the recent debate (like the upcoming ban on transporting chilled sausages between Great Britain and Northern Ireland) would be left untouched.

The Swiss model by contrast would substantially resolve many of these issues but the UK government rejects this outcome, refusing as a point of principle to engage in anything that might resemble European integration, even in the most limited scope and most pressing cases.

Instead, the UK is asking for a Swiss outcome on New Zealand terms. It is a return to the classic cakeism that has consistently characterised Brexit negotiations, in spite of its inability to deliver any successful results.

So we are left with this groundhog day of UK-EU relations: a bitter war of words, misrepresentation of rules and positions, souring attitudes, the rejection of realistic solutions and the recurring threat of trade war. We may ride out this latest iteration and find a solution without the argument escalating too much further, but in all likelihood this will only be a delay to the acrimonious refrain we have been treated to these past few years.

We can't know when we'll finally wake up from this nightmare. It might take some time. But we must remember that it does not have to be this way. The fact that we and our closest neighbours, people with whom we have shared thousands of years of hardship and triumph, are now regularly at each others' throats is not an inevitability of our culture, history or identity. These are choices that are taken and decisions made. They are deliberate and, therefore, avoidable .

People voice concerns of sovereignty but are we now merely cursed to live in the shadow of our sovereignty's apparent fragility? It is in reality entirely up to us what we do with our sovereignty - it will not vanish if we don't show it the proper respect or adhere to the proper dogma. It is not a well that might one day dry up. It is a tool we can use, an option to achieve the policies and outcomes that bring the greatest joy to our nation.

Even if dynamic alignment with a certain set of EU rules in a few specific areas would diminish our sovereignty, would that really be so injurious? Compared to the anger and strife that is tearing at the fabric of our union and poisoning our relationship with the rest of Europe, it is surely a small price to pay. Indeed, it is not merely a wortwhile cost, but an actively positive decisions that we undertake of our own free will - a deployment of sovereignty to the evidently noble purpose of preserving the British union and the peace settlement in Northern Ireland. If only we had the courage to be the masters of our sovereignty, rather than its prisoners.

Comments

Post a Comment