What if Brexit was a generational, not national, destiny?

Since 2016, much time and attention has been devoted to explaining why the UK voted for Brexit - an outcome that few had expected prior to the even itself. One common explanation is this: we were always heading in this direction.

According to this theory, Brexit was, in some sense, an inevitability. The ideal of European integration clashed with something inherent about the British people meaning that, as the project progressed, so we would move away.

It is a straightforward explanation and a beguiling one because it allows us to easily correct for the improbable.

When looking back, we are inclined to believe that things were likely to happen a certain way because they did indeed happen that way. To pick just one example, Trump's election went from a fairly unlikely event to a gospel truth of the inevitable populist backlash to the previous two decades of globalisation. Many chose to believe they were simply wrong about his victory being unlikely and that it must mean be rooted in essential structures that were leading up to this moment all along. We can revert back to what we know to be true: likely events are, by definition, what normally happen, and in turn avoid a more complicated assessment of how to deal with the arrival of the unlikely, of the unpredictable. Brexit has been given much the same treatment.

But it is not obvious that this account of the UK and its departure from the EU has ever passed the sniff test. A claim to uniqueness in these isles can only be properly argued if it is compared to other, similar countries. Yet comparisons are rarely found in discussions of the UK's supposed difference from its neighbours.

It may be true that the UK has a tendency towards national exceptionalism but so does France. The UK may well be dubious about fiscal integration, but so are the Netherlands and Germany. It may have a history of empire outside of Europe but so, to varying degrees, do Portugal, Spain, Italy and France. The typical traits that are assigned to the UK in the narrative of its national destiny are not often unique to the UK at all.

The UK did make certain choices around European integration that others did not but that does not mean that the characteristics of our national character drove us to necessarily make those choices. And if these decisions were not determined by the essential qualities of our place of birth, then it is fair to say that we could have made different choices in the past and, importantly, that there is no particular reason to believe that we will not make different choices in the future.

Because the future is in fact the next step in these arguments. The attempt to establish the causes of past events is not merely an academic exercise - we use it to try and open up a window to what will happen, to understand or even predict the course of the future.

And in politics, if a particular narrative of the past and its reasons can be established, then we can set the contours of the debates that are to come. If people are generally brought to believe that something is inherent, natural or inevitable then they will be less willing to challenge it, more likely to seek some next-best alternative. Why fight the inevitable?

Our understanding of the past is therefore used to guide our future.

So for anyone who has an investment in wanting the UK to take a particular political direction, to exercise certain choices going forwards, it is important to point out that the UK's national tendencies are not all that unique and do not provide adequate explanations for why the UK has made the choices it did - and therefore should not be used to inform what choices the UK will make.

All that said, the claim here is not that events are random.

It is fair to say that there has been a consistency to the UK's growing euroscepticism over the 40 years of its membership of the EU. The argument here therefore is not that there is no rationale at all but that the question has been approached from the wrong angle - or, arguably, dimension.

Rather than thinking about the place of Britain, we should be thinking about time. Rather than reflecting something intrinsic about the UK as a nation, something that is particular about geography (and therefore to all the inhabitants, past, present and future), we may instead be looking at something intrinsic about a specific generation of Brits, something that is particular about a select number of decades in our history.

This brings us to the title of the piece - what if Brexit were not the UK's national destiny, but merely the destiny of that generation of Brits who have exercised a steadily growing influence over our politics during the last 40 years and who, in recent elections and referendums, have been the most powerful voting block?

Put another way, it is not that the UK's particularities make most of its citizens a certain way on the question of European integration but that a (roughly) single generation's particularities made the country a certain way.

We can see evidence of this in the way that the European question interacts with age in the UK.

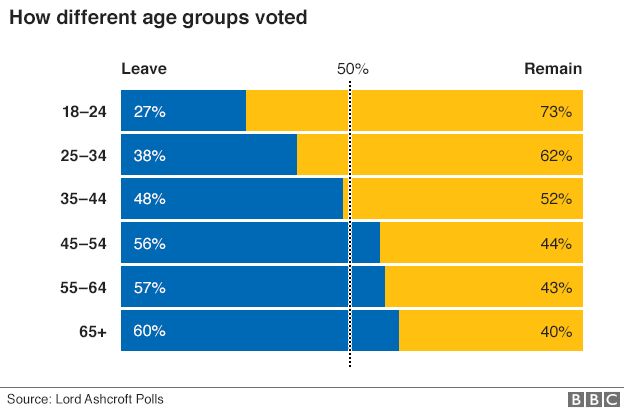

At this point, it's fairly well known that there was a strong relationship between age and the way people voted in the EU referendum. The older you were, the more likely to vote Leave and vice-versa.

What perhaps fewer people know is that this correlation was the reverse of how the vote went back in 1975, when the UK held its first referendum on joining the EU (then the EEC).

Here it is older voters that are more likely to vote to join and the youngest generation that was most likely to vote against.

And, given the amount of time which passed between the two referendums, what we can observe is that the oldest group in 2016 and the youngest in 1975 are in fact more or less the same set of people.

Now of course the numbers do show that some people would have changed their minds over that time but it is fair to say that this is a group of people who have been consistently more eurosceptic than either their parents or their children or grandchildren.

Not the embodiment of our national character but its anomaly.

In this understanding, it is less that Britain 'flipped' from being clearly pro-Europe (67% to join in 1975) to being somewhat against (52% to leave in 2016). It is more a reflection of that group which were never especially keen on European integration becoming more powerful over time. And as they have gained in power and become an ever more essential voter constituency, they have become more emboldened to demand their preferences in absolute terms.

In this sense, Brexit won not because the UK was the place where it could win but because 2016, when a disproportionately eurosceptic generation made up the biggest group of high turnout voters, was the time when it could win.

And if we return to the earlier idea, that we analyse the events of the past in order to inform and shape our future, then this change of perspective has notable consequences.

If we have been living through the height of the power and influence of 'generation Brexit', then what will follow is a waning of that power. If this way of looking at the UK and its actions is correct, then a revived Europeanism should follow. Indeed, there may even be a disproportionately pro-European sentiment - a backlash to the excesses of the current period.

This shift would not even be a process of many decades. We are not that far from the tipping point.

At most it could take around 15-20 years but it could easily take as little as 5-10.

Though some may be reluctant to believe this is the case - dismissing it as wishful thinking - there is already some evidence that this groundswell of pro-European sentiment is real and robust.

A recent poll showed that Rejoin had a 20+ point lead among voters aged under 55. That is not a sullen group who must be tentatively drawn towards changing their views of the EU - that is as sincere an enthusiasm as can be found anywhere in Europe.

And while the numbers are less dramatic, the desire to actually hold a referendum on the issue within the next 5 years was also higher than many would have suspected. Though much of the political discourse in Parliament and in the newspapers argue that the question of our EU membership must be put aside for a substantial period of time, many citizens themselves have no such qualms. It's an important reminder, while politicians may think in terms of 'generational decisions', those decisions are only generational if the public view takes that long to shift. If the public wants something before then, they will not force themselves to wait an arbitrary amount of time. The people are not concerned with betraying their own will.

For some, this may be an interesting but abstract argument. But as mentioned already, the difference between these perspectives and our understanding are more than academic.

I’m a strong Remainer/Rejoiner, but it’s a truism that the change will need to come not only in the UK, but among the EU countries. The damage done to the country’s reputation by the Brexiters will have to be repaired, and that repair will not start while we have a government of Brexiters who, day by day, are wreaking more damage.

ReplyDeleteEven if public opinion swings further and further to Rejoin - and I believe it will - having a government in power that wants to rejoin, or at least is willing to put this to the voters, is a necessary pre-condition.

Opposition parties are weak and appear unwilling to cooperate for the greater good, and until they do, it’s hard to see Rejoin on the horizon.